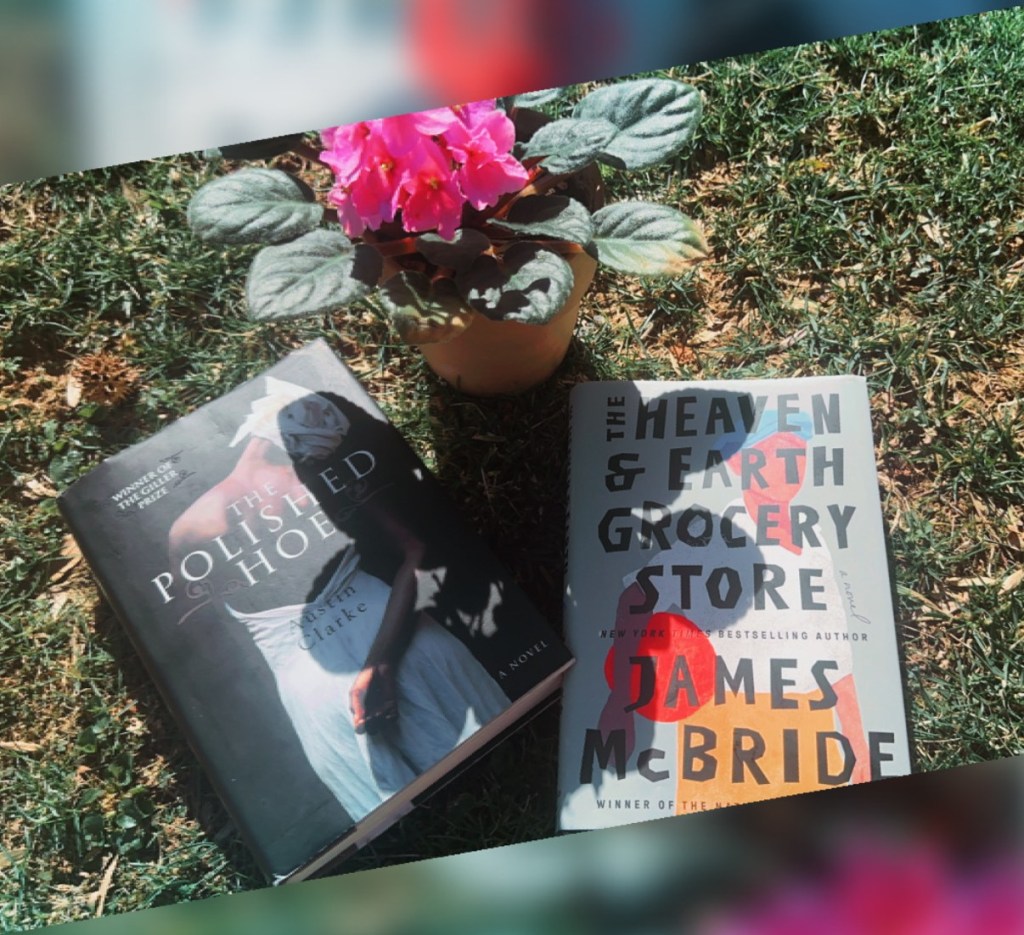

Richard Wright’s opinion of Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God was that the novel fell short of its political duties. He wrote, “the sensory sweep of her novel carries no theme, no message, no thought… Ms. Hurston seems to have no desire whatsoever to move in the direction of serious fiction. Her characters eat and laugh and cry and kill. They swing like a pendulum eternally on that safe and narrow orbit in which America likes to see the negro live – between laughter and tears”. I write this as my daughter watches Percy Jackson; the portion of the movie where Medusa declares that eyes are the window to the soul and is successful at turning a rightfully frightened lady into stone…once her eyes are opened to the snakes upon Medusa’s head. What we are able to gain from a novel (or from anything) has much to declare about our own viewpoint, experiences, fears, weaknesses and strengths. It is cyclical; a give and take, an in and out…until it is not. 2025 is a heavy year and we are not even two months in. It is a political year; a year that needs to be reclaimed. This year already feels like Richard Wright’s scolding of Hurston’s novel. It feels like a man’s world. It feels like HIStory won ‘The Battle of Back to the Future’. Ugh. And ugh again. And thus, two books chose me shortly after the start of 2025. As if they were slid under a closed door with just enough light to read: Austin Clarke’s The Polished Hoe and James McBride’s The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store. Both reminded me that the male gaze can be beautiful in its realness…period(t). Both brought up the question: is there still time to stop and smell the roses while moving in the direction of serious fiction…or serious reality?

The word that kept coming up for me whilst reading both books was: transactional. Transactions are all throughout both works. This cannot be what Dick Gregory meant when he proclaimed that, “once you put on the magic glasses, you see things as they are”: https://youtube.com/shorts/euWo5M3ZFV4?feature=shared Unfortunately, I think it is exactly what he means. The Polished Hoe expands upon this transactional notion by the obvious play on words in its title. And so does McBride’s title. Both examine community – the building of, existing within, maintenance of and even the tearing down of such. What is allowed to seep through the community walls in an effort to keep said community afloat? Did we and do we still need the seepage? Are we still in the business of buying and selling…humanity (of all things)? There are strangers in everyone’s house in 2025. Medusa’s are on the screen, wigs abide in all colors and textures, and known voices echo out of unfamiliar square faces. Magic glasses might be just the welcome mat we need (or not). The truth is: transactions are not what they used to be. This is the good and the bad of it all. And the pendulum is still swinging, and we wish we had the energy to laugh or cry.

The Polished Hoe is set about a warm, sultry Caribbean plantation in the 1950’s with a female main character. The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store spans through the early 1900’s into the 1970’s in the developing faction of Chicken Hill (in Pottstown, PA) and narrates in various voices. Published in 2002 and 2023 respectively, we are reminded that time moves only in one direction – circular. McBride writes in the voice and perspective of Miggy, “their illness is honesty, for they live in a world of lies, ruled by those who surrendered all the good things that God gived them for money, living on stolen land, taken from people whose spirits dance all around us like ghosts.” Even though the worlds within these two books are separated by time, space and climate, most (if not all) truths travel with us; and one might even think they are reading these lines in Clarke’s book. Transactions – to surrender a thing, in a promised effort to gain another. It has gotten so deep into our bones, that our branches are now sharp and metal at the receiving end – shining even in the dark. Transactions are so much our norm, that we shop, buy and sell just to get a mental break. These authors understand this ingrained effort of give and take on a deep level and their narrated, prose illustrations equate to roses emerging from sticking sugar cane and cold concrete (even if one is plotting on selling the rose). The Polished Hoe sets up shop in the smaller houses surrounding the ‘Big House’ – black female bodies and sugar cane become one in the same and keep the cash register making that combined welcoming and exiting sound. And on Chicken Hill, there are many ‘Big Houses’ with titles like Church, Synagogue, Town Hall, Iron Mill and Pennhurst – sometimes you have to be deaf in order to truly hear when the register cha-chings.

The characters in these two books have truly lived. They pull on all faculties in order to survive the storm, chart it, and cover their loved ones. These storms come in the form of unsolicited courting and sexualization, bodily ailments, world wars, genocide and everyday family life. These characters transform in and out of flesh, bone, mind, matter through the lens of objectification. Through Mary Mathilda, we learn that a garden hoe’s value is linked to how well it can be sharpened and polished – if you can objectify something, you can weaponize it. Paper and Miggy teach us that once the objectified become learned, the cash register heads towards its own victimization before becoming all but obsolete. Everyone has a role that they play in infiltrating the Big Houses in an effort to… reframe them. Upon arriving at their helms, eyes are truly opened. And each author allows their characters (through the touching of another) to hold tight to a slippery and slipping humanity along the way.

Clarke writes, “it is a contest. There is no interest in the rightness or wrongness of a murder case.” And we are confronted with the utterly mean games we play at the front steps and back doors of the Big Houses. This blow is made bearable by the two bookends holding Mary Mathilda upright – Percy (a childhood friend turned township police sergeant) and Wilberforce (her well traveled, well educated son). Both know her because they are of her; and thus understand her to a certain degree. The understanding comes after the knowledge and all cash registers are silent when the two meet to create empathy. Mary Mathilda is human. Never mind the polishing of blades and wood or what it takes to survive cane fields and spying glasses from on-high. Percy’s respect and desire for Mary Mathilda is evident. He shows a deep patience for her story despite the obvious dread to carry out this duty of taking her statement. Finally, we learn that the law proclamation holds true – an eye for an eye, a life for a life. Transactions.

McBride writes, “but the loss of hearing had not decreased his love of music. Indeed, it had intensified it. / It was as if the magic of the hymn Dodo offered up had marched into the room.” And we see a transaction that can’t be bought, sold, mishandled – a transference of pure energy. We see magic…unpolluted. Through the interactions of Dodo and Monkey Pants, a fractured community is personified: a little white fella all balled up into a neuro knot and a motherless black boy post various literate and figurative explosions. A state of survival becomes something totally different once innocence is on the line. Just because a little boy cannot hear the music, doesn’t mean he cannot feel the beat and the rhythm and learn the movement of your lips as you sing the lyrics. So, we become more careful at what we produce when crippling one faculty only enhances another. An educated transaction.

If the characters in these novels were vegetation, they would be root veggies. If they were animals, they would be doe and bucks. If they were crystals, they would be soft pearls. Mary Mathilda and Nate Love – diamonds all the way. If they were directions, they would be annular – a north and south flipped on its axis, trying as it might to still work through memory and feel. They existed in times that had no space or inclination for highlighted pronouns, mental health diagnoses or even blog posts. They were Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston – both looking upon the garden hoe but seeing different value; borrowing each other’s eyes because the sun is just as blinding as the dark. Trust can exist in transactions. I think Richard Wright knew this. I think he needed it to be so. But, trust can exist outside of transactions; and I think Hurston knew we are in dire need of this being so. If we are to watch God, the zeros and ones would surely make us cross-eyed. Thus, McBride and Clarke paint with brotherly love and sugar cane, in all its HIStory. And they both get it – the selling of humanity and the rectification; how certain ideals had to be gazed upon before being placed underneath the pendulum. The main characters swing and they do not miss. The heroes and heroines are everyday, ordinary people – deep as roots and buildable as expanding pearls. Their mistakes were preceded by a passion that linked up with the end of the road and bid us a story of invaluable wisdom before letting go. Well done. Well done.

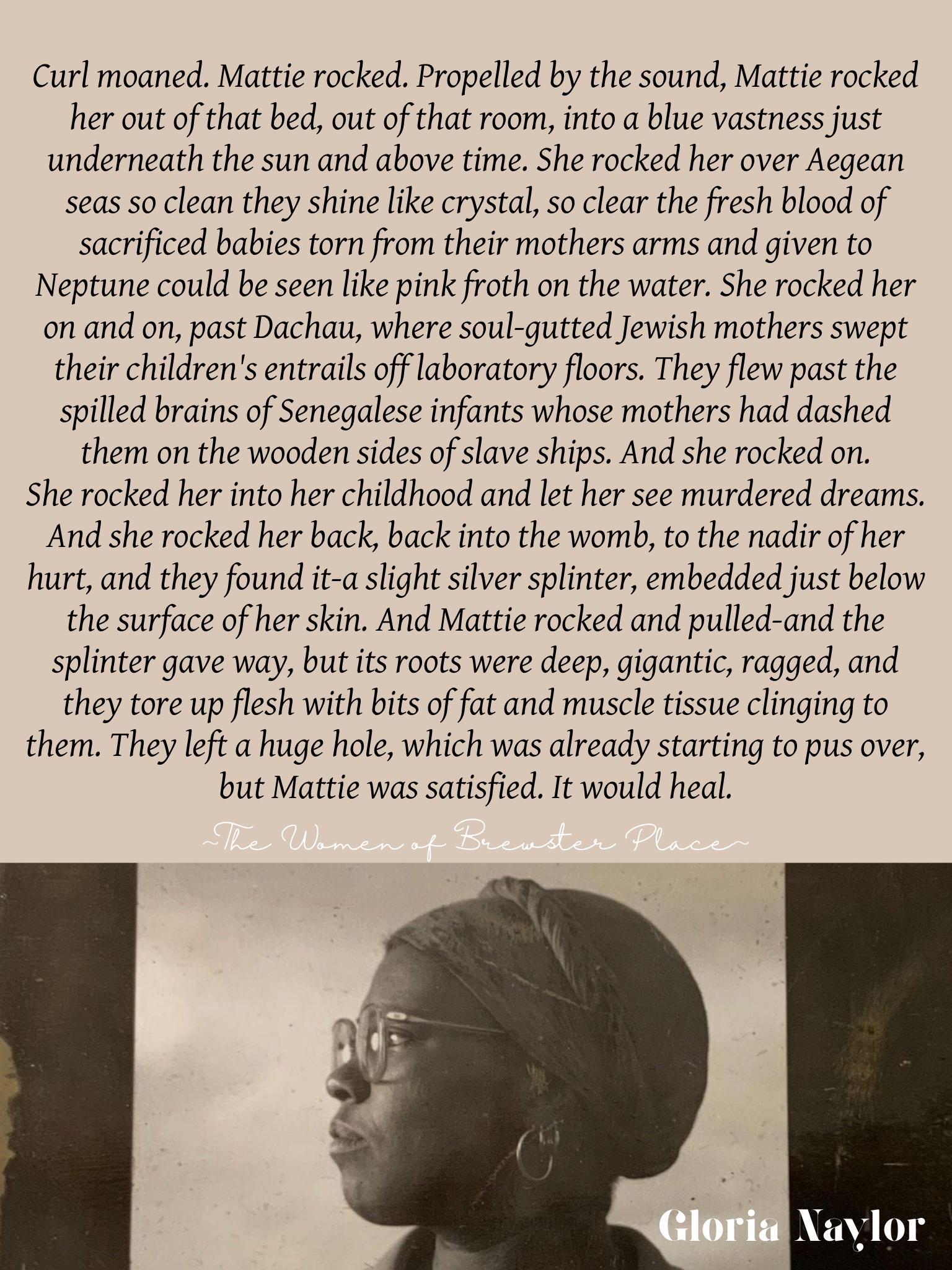

A few questions before and after your read: (1) In my opinion, these characters (in both books) exhibit a certain level of respect for self and others that I find suited to and exuded by (black) male authors. How might this outlook change if written by a female author? (2) Alice Walker writes, “In search of my mother’s garden, I found my own”. In search of your father’s Big House, what might you find? (3) Institutions play a large role in both of these works. Are our institutions more than just the buying and selling of goods? Why or why not? (4) Who are today’s polished hoes? (5) What are today’s Heaven & Earth grocery stores? (6) Are the killings in each book…necessary? If not, what else could have been done? If so, how do we rectify ‘thou shalt not kill’? (7) Chona and Moshe have somewhat of an arranged marriage. How do you feel about this? (8) How are the unmarried women in McBride’s book portrayed; and what are their options? (9) Is it just me, or did you ask yourself what in the world was up with Wilberforce? (10) Why did I end the review with this particular excerpt from Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place? (11) We speak a lot about the objectification of women (and rightfully so). But, how are the males objectified in both novels? (12) How does one break free of the value placed upon their heads by outside forces? Is it even possible? At the conclusion of each novel, are Mary Mathilda, Sergeant Percy, Nate Love, Dodo, Monkey Pants now…free?

Citations:

Clarke, Allen. (2002). The Polished Hoe. Canada: Thomas Allen Publishers.

McBride, James. (2023). The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store. United States: Penguin Random House.

Wright, Richard. (1937, October 5). “Between Laughter and Tears”. New Masses. https://www.dentonisd.org/cms/lib/TX21000245/Centricity/Domain/490/Richard%20Wright%20on%20Hurston.pdf